This is both a review and a plea.

Mostly for my fellow Jews who are devastated by what happened on October 7, rightly terrified about growing anti-Semitism, feel a deep connection to Israel, but also know that what is happening there and to the Palestinians of Gaza is horrifying, unwinnable, unsustainable, and most of all, unjustifiable — that it is destroying the soul of one people as it destroys the body of another.

I ask that you read this and withhold judgement and defence until you reach the end. Then we can talk.

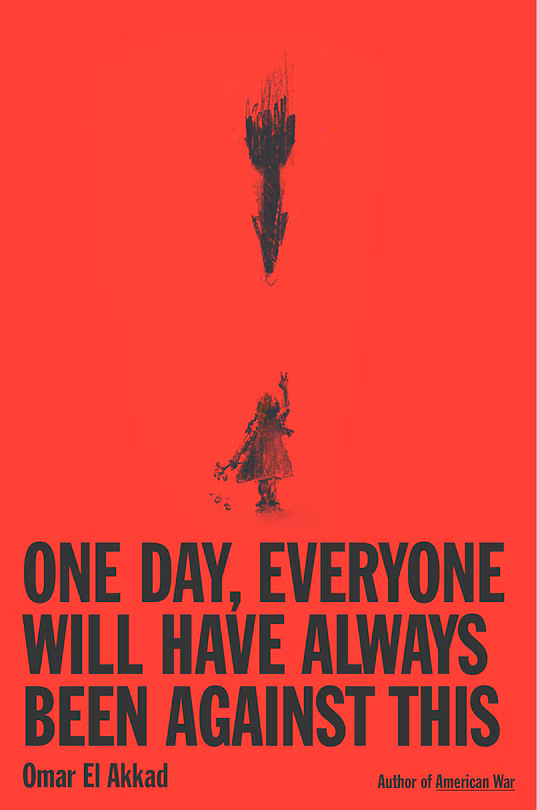

In One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This,

applies sublime poetic prose sprinkled with edgy self-deprecating humour and penetrating critique, as much to the description of an eighteen month old Palestinian child with a “bullet wound to the forehead”, as to quietly dismantling the hypocrisy of Western liberalism. The author lays bare his own ongoing complicity — a life full of awards and accolades care of his adopted countries, Canada and the US. He doesn’t use depictions of the horrors that open each chapter as a dogmatic hammer. Rather, he extends a gentle hand and invites me (I’ll let others make their own decisions about their invitation) to join him in this brutal and deeply disappointing place.There were hundreds of people at Isabel Bader Theatre, the first of two sold out events in early March, for the Toronto launch of One Day. It struck me that even if El Akkad packs hundreds or thousands of medium-sized theatres around the world, his book may still not make a difference. The powerful narrative he so beautifully shreds, the apologia that allows Western liberals to throw ourselves with whole hearts and shining righteousness behind what will only ever be the lesser of two evils, is so pervasive as to be invisible. El Akkad understands that.

Omar signed my book For Aviva, with love.

Omar signed my book For Aviva, with love. I don’t care that every book he signs says with love. It still feel personal and sincere. It says I love your willingness to go there with me. I like to think my Hebrew name made it all the more meaningful to him in the twenty seconds we shared.

I admit, while reading One Day I looked for crumbs of empathy for my people, but prepared for the worst. Maybe I’ve softened or hardened over the past year and a half. And maybe it was my choice to not feel attacked. But I didn’t. There were a few kind words for us Jews and I took them. Not everything requires balance.

I want to bring El Akkad to Beth Tzedeks and Holy Blossom Temples across North America, even if what he’s saying is hard to hear. Not just the violence, but the proposition that we let ourselves be duped and look away, while pretending not to. If we are unwilling to see the suffering of others, how can we expect others to see ours?

“Fear”, he argues, “causes the world to flower in limitless terrible possibility.”

One aspect of the author’s analysis that struck me, and which I now blab on about at any opportunity, is the notion of fear as currency and the disparity in its exchange rate. “Fear”, he argues, “causes the world to flower in limitless terrible possibility.”

He talks about his own fear of things like large US flags on pickup trucks in rural Oregon where he now lives. “My fear buys nothing. I expect it to buy nothing…And yet I know other people’s fears — as irrational as mine, more irrational than mine, buys everything. It moves armies, obliterates thousands.” He talks about “terrorism” being the exclusive domain of Brown people.

When a White man kills dozens at a concert, a synagogue or a school, it’s a crime, sometimes a hate crime, but not terrorism, which he says “requires a distance between state and perpetrator wide enough to fit a different kind of fear. The kind of fear that justifies the creation of entirely new laws, new modes of detention, new apparatuses of surveillance, anything, anything at all.”

El Akkad’s book was finished before the re-election of Donald Trump, but the actions of his regime, now perpetrated so glaringly on US soil, make it impossible not to agree.

The thing about fear is that it’s always legitimate. It’s a feeling, not a fact, so it can’t be dismissed. Although Jews these days keep being told that our fear of anti-Semitic attacks which statistics indicate are hugely on the rise in Toronto and globally, are inflated beyond rational expectation.

Sometimes fear is based on what is happening now. Sometimes it’s due to decades or centuries of trauma, oppression, and waiting for the next shoe to drop. And sometimes it’s about the possibility of losing something you think you’re entitled to, by virtue of being, for instance, White.

…my fear becomes problematic when it blinds me to the actual terror faced every moment of every day by others.

I understand fear. I’m a fear-first kind of gal. But don’t tell me it’s a figment of my imagination. That said, my fear becomes problematic when it blinds me to the actual terror faced every moment of every day by others.

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This offers no clear solutions. (I so badly want to be told what to do.) It leaves us sitting uncomfortably in what El Akkad has exposed about the countries we believe to be the best places in the world to live. And they may very well be. And yet there it is, laid bare, the privilege of our own collusion, detachment or indifference.

One Day invites us to open our eyes.

Can we do that? And then can we talk?

I've been playing with the idea that it's not fear that is the problem, rather the self-righteous justification of violence and abuse of power that comes out a sense of victimization. As with your discussion of fear, there is usually a factual basis for feeling abused and often a legitimate claim for redress and institutional change. It is when victimization becomes the foundation of one's ethnic identity that true problems arise because then power acquired is used to victimize others with no transition to toleration of differences in sight.

So glad you wrote about this. Not easy. But so vital. And so well done.